We woke early Tuesday morning to begin the trek to the village of Enayetpur, where we’d be conducting the training. On Monday afternoon a second team arrived consisting of a cardiac surgeon, a perfusionist, a physician assistant and an OR nurse. Their goal was to train the local surgeons in improving their techniques and efficiency. So a little after 7 our 3-hour drive began to Khwaja Yunus Ali Medical College & Hospital located in Enayetpur, Sirajganj, which northwest of Dhaka. A packed mini bus took both our team and the surgical team along with our local contacts to the hospital.

We finally arrived around 10:30 to a welcoming of hospital staff and flowers. Following that greeting we settled into our rooms, grabbed lunch then began prepping for the rest of the week. We also met the founder of the college and hospitals son, Mohammed Yusuf. A man proud of his father and what they are achieving, he has a calming/authoritative presence that makes you simultaneously feel at ease and want to sit up a bit straighter. The campus itself lies on 180 acres of land and 90% of staff live on the grounds (with their families if applicable). In addition to the medical college there’s also a nursing school and a school for the children of the staff who live on campus.

The campus is a nearly self-contained community with an organic garden, double filtration system to provide clean water throughout the campus, and its own power generator.

Yusufs father was a serial entrepreneur, as is Yusuf and the funds from these various business ventures subsidize the hospital. Patients are treated regardless of their ability to pay and are charged on an income-based sliding scale. In a country that doesn’t have public health insurance and is only private pay, where an income of $500 USD/month is considered middle class, this is an incredible benefit.

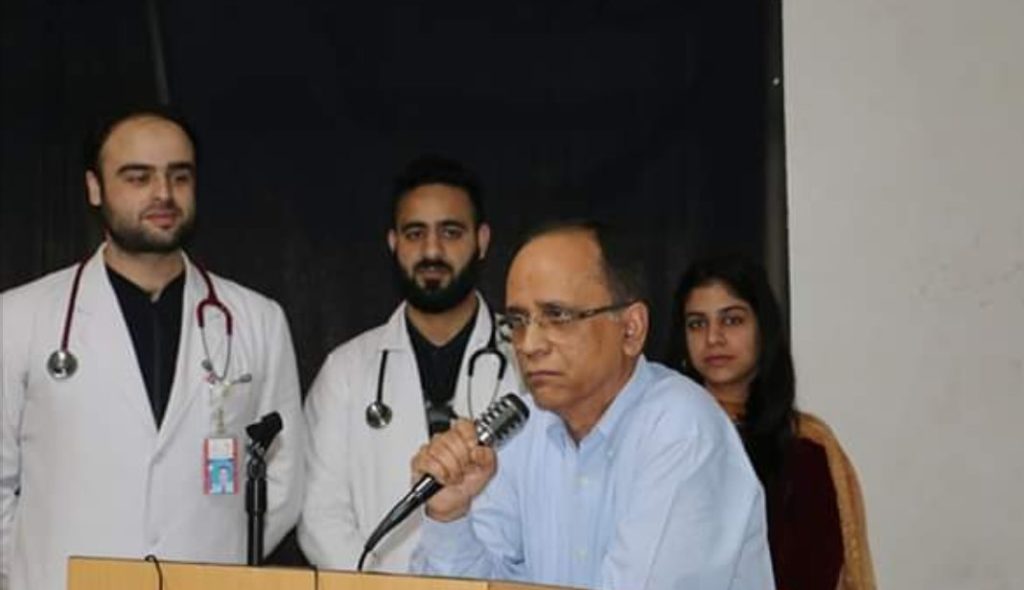

Following lunch was a short ceremony where some of the hospital dignitaries spoke and thanked us for coming. We also introduced ourselves and thanked them for inviting us.

We toured the hospital and grounds with Raju, an anesthesiologist there. As we toured around, we were impressed with what we saw. There was an outpatient clinic, which was clearly quite busy, their radiology department with x-ray, CT and an MRI, a general ICU, cardiac ICU, general medical/surgical wards, pediatric ward, and emergency department. Their monitors and pumps were like anything you’d see in a Western hospital. On the other hand, their lack of defibrillators throughout the facility was a concern. Should the ED need one, for instance, they had to call the ICU to bring theirs.

One critical component of a hospital, and the reason we we’re there, was how a hospital responds to a patient in cardiac arrest, also known as a “code”. A typical response is for staff to start CPR and a team of people to respond to where the patient is to provide more advanced care. Here, the protocol is to bring the patient to the code team in the cardiac ICU.

Armed with this insight and knowledge, we began prepping for our first class. One adjustment we needed to make revolved around equipment. We wanted to run this according to AHA standards but our missing bag still hadn’t made an appearance. We needed to adapt and design a classroom model to teach a total of 54 students (18/day) CPR with 2 adult manikins, 1 child manikin and 1 infant, oh! And 1 AED. American Heart Association standards say we need a 3:1 student to manikin ratio and a 3:1 student to AED ratio. We needed to design something to work within those parameters.

Fortunately, when we met with the owner of the AHA training site in Dhaka on Monday, we mentioned our shortage of equipment and he was able to pull together some bits and pieces for us to borrow. On Tuesday afternoon we confirmed he was going to bring the needed equipment and we structured class to meet the AHA demands. We tried to crash early, day one of teaching was coming fast.